Vision Unfolding

Years later, I realized my

work in progress began

there, at that dinner

table. It was there that

the hook was set.

by Jeff Smith

Hourglass Founder

by Jeff Smith

Hourglass Founder

SETTING THE HOOK: Circa 1975, I was 12. The dinner table at the old manner house at Schramsberg was full of chatter. The three Davies boys and I engaged in the kind of banter pre-teens revel in, a dialect of slang and topical references known unto us, a foreign language of sorts. From the head of the table, without missing a beat, Jack Davies interjected a witty and poignant comment in our tongue. All four boys, jarred out of our self-absorbed discourse, were now engaged with an intriguing interloper. Something unexpected: An adult speaking our language? The ensuing minutes were a serious parlance of delightful and hilarious repartee in teen-speak. Who knew our private language could be deciphered, our codes cracked?

But Jack Davies was a unique individual and skilled linguist. He was one of the early pioneers of the modern wine business, someone my father had befriended and showed around Napa Valley in the mid ‘60s, long before Napa was on anyone’s radar. Jack was a smart risk taker, a visionary, a jazz musician turned corporate executive turned corporate exile turned winemaker. What he lacked in experience he made up for in drive, a winemaker to take Napa head on as it emerged into the stuffy echelons of class and pretense that so defined the haute world of wine at that time. Americans were about ready to lay waste to the upper crust of wine society and redefine it for good. Jack was game. He had discovered a different language.

What California winemaker thought that way in 1966?

Years later, I realized my work in progress that ultimately became Hourglass, began there, at that dinner table. It was there that the hook was set. Jack and Jamie Davies’ stories of the day, told with a wry sense of humor, a blunt homesteader’s honesty, and a soothsayer’s imagination. Jack could look into the future and vividly describe it, or simply recount the mundane trials of the day, bootstrapping his way through the nascent stages of a wine industry yet to unfold. What balls it took! He envisioned an American Champagne to rival the French. Really? Who the hell thought that way in 1966? The only other person to think in those terms in the mid ‘60s was Robert Mondavi who had an infamous explosion with his family and their wine business, Charles Krug, in 1965. The fracas was largely driven by Robert’s intense desire to put Napa Valley on the wine world map, and the family’s modest belief he was putting on airs. That was the year after we moved to St. Helena and a year before the Davies bought the old tattered Schramsberg estate.

They would "borrow" a riff, a melody, a cord structure, but when they conducted their sound it would sing uniquely to them.

THE VOYEUR: After those stories at the Schramsberg dinner table, it would be nine years before I’d have the opportunity to work for Mr. Mondavi, the next evolution in my unfolding journey. It was here I would learn the importance of crafting a strong vision. While chasing a music career in my early 20s, I took a lowly job at the Robert Mondavi Winery (RMW). Like my time at Schramsberg, this exposure to the profession would slowly and surreptitiously hijack my soul to determine my fate and define my work in progress. My learnings there would set the hook deeper.

I was used as sort of a “utility infielder,” a guy plugged into whatever hole needed plugging. Ultimately, I could not have been given a better vantage point. Mondavi had a unique culture—openness unlike anywhere. I was able to interact with the senior decision makers as I went about setting up their tastings and doing their bidding. I was a voyeur, a fly on the wall of no consequence, but one with keen ears and wide eyes. What better perspective to learn a trade than from some of the smartest and most dynamic people in the business?

The late ‘80s were the golden era of Mondavi: Pre-IPO, unfettered self-determination, a dogged focus to push wine quality, driven by Robert’s intense charisma and infectious desire to learn, improve and lead. Culturally, Mondavi was firing on all cylinders, vamping off of the discovery and explosion of the burgeoning American food scene and fusing wine with art, architecture, politics, music and more. Like Jack Davies, Robert Mondavi was his own man. In the way that Jagger and Richards would lift lines from American blues and soul greats to inform their sound, the early wine pioneers like Jack and Robert would learn from others. They would “borrow” a riff, or melody, but when they conducted their sound it would sing uniquely unto them.

With that California Indian summer, one might dare hang grapes longer. What would happen?

THE PARADIGM SHIFT: The ‘70s and ‘80s were a period of learning. The great experimentation of Napa started as a borrowed riff from other wine cultures steeped in hundreds of years of tradition and far flung terroirs. Our winemaking pioneers were not “of wine." They had no generational passing down of knowledge that was the life’s blood of centuries of learning in other wine cultures. In true American fashion, however, naiveté was an asset: Who would try their hand at this if they really knew what was involved?

Their naiveté was augmented with a spirit of intense problem solving. If those early vintners didn’t know what to do that wouldn’t stop them, they would just find someone who did. So the likes of André Tchelistcheff, Walter Schug and Mike Grgich began consulting the newbies. These were men trained in classical European winemaking and the wines of the ‘70s and ‘80s reflected these virtues. Yet, the terroir of Napa bore little resemblance to the Old World: a mind boggling array of soil types, multiple climatic zones in a small geography, a longer growing season, diurnal temperature swings of hot and cold influenced by marine fog, the mountains, valley floor, on and on it goes…These complexities did not always square with the traditions perfected in the Old World specific to those regions.

My awakening came amidst the paradigm shift. The experiments of the ‘70s and ‘80s, along with vestiges of traditionalism, were giving way to a new school of thought. With Napa’s longer growing season, one might tempt fate in a way unimaginable to the traditionalist. With that California Indian summer, one might dare hang grapes longer. What would happen? The traditionalists were schooled by climate, or chemists, not to hang fruit beyond 22 degrees brix (a measure of sugar content), or push beyond the 3.6 pH barrier, much the same way the seafaring circumnavigators were told they would sail off the edge of a flat earth. Some dared and found new worlds. So, too, did a new generation of Napa winemakers, pushing the envelope to unlock new expressions of a collective work in progress. A new vision of Napa was unfolding and I wanted to be part of it.

There are demons there, the traditionalists would argue.

TRADITIONALISM TO MODERNISM - STYLE AS A SPECTRUM: As it turns out, this new vision, or at least my part of it, is really a personal historical journey, sliding across a spectrum of discovery to find the stylistic Holy Grail for Hourglass. The aim, as I saw it, was to discover what Napa was about, why it’s so unique, and bring from it wines of unique personality that are an interwoven reflection of a specific place and a singular artistic expression—a culmination of the myriad decisions we make farming our vineyards and crafting our wines. Sliding on the spectrum became an exercise in shifting from traditionalism to modernism to fully explore what each meant. Only then could we move beyond both to a state of postmodernism, learning what to keep, discard, and refine, and discovering how to balance new findings with old traditions.

“Style” is a word many winemakers generally abhor. Why, I’m not sure, but perhaps it implies something trendy, or fashionable, thereby rendering it a bit fickle. Maybe, but I see it differently. In my view, style reflects the end result of intention. If your intention has clarity and purpose, then your style should as well. Having a clearly articulated style seems critical to me. That’s easier said than done, especially for a culture still finding its way.

Until the ‘90s, no one in the world had really explored the upper reaches of breaking the 3.6pH barrier as an intended wine statement. There are demons there, the traditionalist would argue. Microbial demons lurking in higher pHs. Instability, inability to age, the god forbidden specter of high alcohol, etc.

Well, a few brave souls decided to head out to sea: Helen Turley, John Kongsgaard, Bob Levy, Heidi Barrett, Craig Williams, and David Abreu, among others. And, of course, there was my early mentor Bob Foley. They were the game changers. They went where they were told not to go. “There’ll be microbial serpents there.” They changed the whole thing, ushering in a completely new style of winemaking.

What happened was a new understanding of what constitutes ripeness.

It largely started in the vineyard with new farming techniques spurred on by the ravage of phylloxera in the late ‘80s, paired with a focus on growing wine as much as making it. There emerged a recognition that if terroir (the influence of environment on wine) exists, and our terroir is different, shouldn’t our winemaking techniques take that into account? If we let grapes hang longer in the Indian summer, what could happen?

What happened was a new understanding of what constitutes ripeness. Prior, ripeness had been defined by sugar (expressed in degrees brix) and acidity with its relationship to pH. The new school of thought began to play with the accepted boundaries by hanging fruit longer, and pushing sugar up and acidity down (sugar/acid are inversely related in the ripening process). The results were interesting: deeper mouth feel, silkier textures, fresher aromatics, more fruit expression, higher alcohol (don’t get me started on the vast amounts of misinformation on this subject), longer finish, etc. Most importantly, no one died being eaten by a serpent! If a little is good, the thinking went, maybe a little more is better? Thus the pendulum began to swing into modernity and my work in progress began to accelerate with that four-acre vineyard my Dad had the great fortune to stumble upon. Hourglass was on its way as an early player in the new movement.

Keep in mind the Hourglass Estate is an amazing little vineyard. Due to its unique geography at the pinch of Napa Valley, it has a built-in climate regulator influenced by the cool afternoon breezes created by the constriction of the mountains. Over the years that little vineyard has taught me a great deal about wine. It’s helped frame and inform my thoughts.

When we acquired the Blueline Estate with our partners in 2006, I expected it would take 10 years to really figure out the vineyard. True to form, it has. A warmer site compared to Hourglass, we started out employing the same farming and winemaking techniques. We also followed the logical extension of sliding to the farther reaches of modernism on the style spectrum. We learned a great deal in the process. Our wines took on weight and traded vitality for intensity–monochrome versus Kodachrome. I see this as neither good nor bad; the wines were well-crafted yet, stylistically, I felt there was more in these wines to unfold. I make no apologies for extending to the far reaches of ripeness, though I ultimately came to the conclusion it was not the place to reside. I like vitality in wine. Edgy acids in relation to richness create a tensional yin/yang that brings the palate alive, expresses drama, provides layers of complexity and contributes a red fruit characteristic against the black fruits of a higher pH.

I also like an expression of minerality when it can be achieved. Both our vineyards have noticeable expressions of it when handled properly. We learned that phenolic mass accumulated by extended ripeness tends to mask minerality and bind the higher tones of aromatics leaning toward the monochromatic. We wanted more.

So how do we apply those learnings to uncover the Holy Grail of balanced proportions?

POST MODERNISM & CHASING THE HOLY GRAIL: To my knowledge, Clark Smith (no relation) coined the term “Postmodern Winemaking." His book on the subject is a must read for those interested in the current state of winemaking. It’s a book that helped articulate the effect of techniques we had begun to implement when Tony Biagi came on board in 2012 to take over winemaking duties from Bob Foley.

Great winemakers have an uncanny balance of left and right brain.

What is postmodern winemaking? As the name would suggest it is an evolution beyond modernism. In our case, a fusion of modern and classical techniques learned as we slid across the spectrum of style. To find the Holy Grail, we would need to apply both. I have often commented that the great winemakers have an interesting balance of left and right brain. Bob has it, as does Tony, but they apply it differently. Bob taught us an enormous amount about higher pH winemaking, which for him seemed an intuitive process. His enduring legacy as an artist and mentor will always be part of our winemaking DNA. His affinity for texture, depth and fruit expression is a hallmark we will continue to refine as we evolve our craft.

Yet Tony represents the refinement phase of our evolution. The attention and precision required to find the Holy Grail requires more time than a consulting winemaker with all the responsibilities of multiple clients is able to give. Having Tony involved in the minutiae—from every aspect in the vineyard to every little step in the cellar—afforded us the opportunity to take our wines to a whole new level.

The refinement of precision is a collection of decisions—some obviously significant, some seemingly inconsequential—all leading to something. It is the sum of decisions made, on the wines schedule and not ours. It’s also the balancing act of art and science, modernism and traditionalism, wound with a good dose of passion, tempered by intellect. Precision is that magical space between, the ultimate vision we seek to unfold.

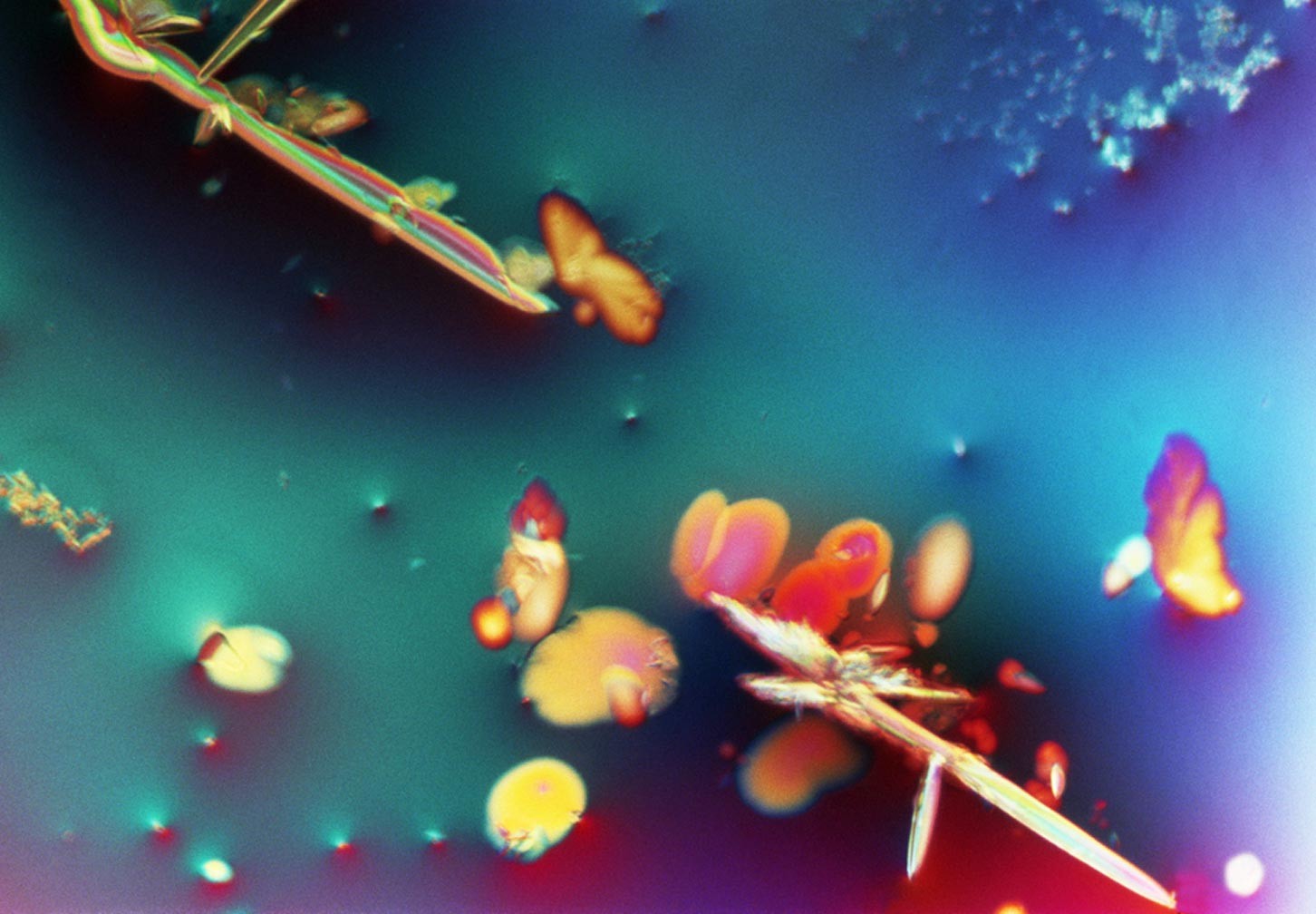

From a technical standpoint, I liken Tony’s approach to building wine inside out. Structure is everything, the core of red wine. Get that right, a finely knitted weave, and everything flows from there. Make no mistake, structure is achieved in the cellar, but it is set in the vineyard. The two halves of a wine’s life must achieve harmony with a balanced chemical equation if structure is to be properly set. If you believe Clark Smith’s technical treatise on the subject, structure is the bonding of tannin with color. As Tony says “color (monomeric anthocyanin) is everything.” This monomer bonds with tannin to cap its reactive ends, stopping its propensity to polymerize (grow) and shortens its chains, leading to a tighter weave as the tannins stack together in a complex architecture to create structure. The shorter the tannins, the more compact, the tighter the weave, the better the structure, the better aromatic integration, the longer the aging cycle… So color is very important in its relation to tannin. Capped tannin also tends to be less reactive with salivary protein, and thus delivers silkier texture. Can you have your cake and eat it too? Can a wine age well and be seductive as young wine? We think so!

What we learned in our modernist phase is that waiting on the vine improved color. If more was better, wait longer. But life is full of trades. To wait longer is to risk a rise in sugar (alcohol), or a loss of acidity. What we actually found with cutting-edge chemistry is color often fades after a certain point. Hanging fruit unnecessarily could reach a point of no return with color peaking then recessing as acid falls and sugar rises. No Bueno if chemical balance is our ticket to the Holy Grail. Through trial and error, and some wise viticultural advice from Tony and our vine guru, Kelly Maher, we began tweaking our water delivery in the field. Holding back in the Spring would induce stress when the plant wants to lurch into its vegetative cycle. Restricting the vine's natural propensity to drive energy to its tips (apical dominance) was something we learned could be very helpful at the onset of growth in the Spring. Stress was good then, but could be a liability later. After the vine has taken the hormonal cue to slow down, and the grapes turn from green to red (a state called veraison), we learned to give the vine strategically timed drinks so it walks a fine line of balance where the canopy remains healthy and photosynthesis can work its magic. The goal being to deliver that balancing point where color, tannin, sugar, acid, and an array of complex phenols are in sync with each other. To achieve that one must engage a viticultural dance with Mother Nature. Get it right here and you have the chance of making profound wine.

Making wine of great personality is not like making Coca-Cola or Budweiser (two things I quite enjoy). Formulas are the realm of consistency, but not of artistry. Chasing the Holy Grail of wine is an art form: ephemeral, complex and ever-evolving. No doubt, the understanding of how we apply our craft will continue to evolve,prodded along by new discoveries and new dimensions of knowledge. Through science and experience, we will see deeper into this complex chemical web that is wine, comprehending new relationships and developing new tools of artistic expression. This vision unfolding does not end here, as quite possibly our best wines have yet to be